Many people argue that prehistoric cave paintings from the upper paleolithic age (50,000-10,000 BCE) mark the earliest form of animation.

Though not actually animated, these cave paintings mark an early understanding of how multiple images can be used to signify movement in the subject, a principle which is the foundation of animation. The multiple outlines of the same animals show an awareness of the persistence of vision which I will return to later.

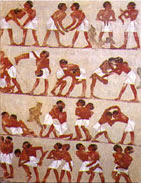

Some seven thousand years later, in Ancient Egypt, similar paintings like this one told stories which were presented as multiple drawings, each "cell" representing the next stage in the story. This is akin to a modern-day storyboard. Though, again, these drawings are not technically animated, they are another milestone in 2D animation's history since we see multiple drawings in chronological order, each representing a different part of the story. In this case, the story is two men wrestling and if we could see the pictures in rapid succession, it may appear animated.

So far, nothing has been actually "animated", only images which represent movement. For something to appear animated, we have to see the individual frames (or cells) in rapid succession.

Below is a zoetrope, "a device that produces the illusion of motion from a rapid succession of static pictures" (Wikipedia, Zoetrope). Its earliest known conception was in China around 180 AD by inventor Ting Haun and was called chao hua chich kuan (the pipe which makes fantasies appear.) The device, which consists of pictures inside of a cylinder with vertical slits in, was driven by convection, meaning that rising air would turn the cylinder and the pictures inside would appear to move.

(a digital version of an animated zoetrope reel)

The zoetrope was revamped in 1833 by British mathematician William George Horner who called it the "deadalum", though it was popularly referred to as "the wheel of the devil". It only adopted the name zoetrope when American developer William F. Lincoln named it so, after the Greek words ζωή zoe, "life" and τρόπος tropos, "turn", thus it was also known as "wheel of life".

Around the same time, Beglian Joseph Plateau established the phenakistoscope which was a disc with pictures around the edge which would create the illusion of movement when the disc was spun.

Both of these inventions, as well as others like them, are based on the persistence of vision theory. This theory states that the eye maintains an afterimage for approximately one twenty-fifth of a second. This phenomenon has been noted by many famous philosophers and scientists, including Aristotle. However, some of Peter Mark Roget's experiments in 1824 are cited as the basis for the theory.

This thaumatrope (as seen below) was used by John Ayrton Parin to demonstrate persistence of vision to the Royal College of Physicians in London in 1824. The invention consists of a disk with a picture on each side. When spun fast enough with the strings, the two images appear to merge and exist as one. It was a very popular Victorian toy as it was simple and fascinating for minds that weren't used to moving pictures like we are today.

This thaumatrope (as seen below) was used by John Ayrton Parin to demonstrate persistence of vision to the Royal College of Physicians in London in 1824. The invention consists of a disk with a picture on each side. When spun fast enough with the strings, the two images appear to merge and exist as one. It was a very popular Victorian toy as it was simple and fascinating for minds that weren't used to moving pictures like we are today.

Paris allegedly based the invention on ideas of the astronomer John Herschel and geologist William Henry Fitton, although some sources credit Fitton as the true inventor.

Persistence of vision and early inventions like these which demonstrate it are hugely important to 2D animation. They are the very foundation of animation. Their conception spawned a new understanding of how the human eye worked and how it could be tricked into thinking pictures are moving. Suddenly, a world of possibilities opened up in which animated pictures could move away from the novelty toy category and move onto the big screen.

In 1877, Charles Emile Reynaud invented the praxinoscope. This was the successor to the zoetrope and, "like the zoetrope, it used a strip of pictures placed around the inner surface of a spinning cylinder. The praxinoscope improved on the zoetrope by replacing its narrow viewing slits with an inner circle of mirrors, placed so that the reflections of the pictures appeared more or less stationary in position as the wheel turned. Someone looking in the mirrors would therefore see a rapid succession of images producing the illusion of motion, with a brighter and less distorted picture than the zoetrope offered." (Wikipedia, Praxinoscope)

In 1877, Charles Emile Reynaud invented the praxinoscope. This was the successor to the zoetrope and, "like the zoetrope, it used a strip of pictures placed around the inner surface of a spinning cylinder. The praxinoscope improved on the zoetrope by replacing its narrow viewing slits with an inner circle of mirrors, placed so that the reflections of the pictures appeared more or less stationary in position as the wheel turned. Someone looking in the mirrors would therefore see a rapid succession of images producing the illusion of motion, with a brighter and less distorted picture than the zoetrope offered." (Wikipedia, Praxinoscope)

Simarly, in 1879, Eadweard Muybridge created the zoopraxiscope. This is considered to be the first movie projector. It worked by projected images from glass panels. The images were originally drawn on and were later printed on photographically and then coloured by hand.

In 1889, Reynaud improved on his praxinoscope by developing the Theatre Optique which was capable of projecting images on a screen. This meant that he could show hand-drawn cartoons to audiences.

Both Reynaud's and Muybridge's inventions were especially significant advancements in animation as they were the direct predecessors of the Lumiere Brothers' film projector.

Auguste and Louis Lumiere were the sons of Antoine Lumiere, who ran a photographic firm and employed his two sons. When their father retired in 1892, they began creating moving pictures. They patented a number of processes leading up to their film camera, such as film perforations which are the holes in film reels that allow the pictures to move easily. These perforations were originally implemented by Emile Reynaud, so we can see how his praxinoscope influenced the Lumiere Brothers. Louis Lumiere also had made some improvements to the still-photograph process, the most notable being the dry-plate process, which was a major step towards moving images.

The first public film show which charged for admission was held on December 28th, 1895, at Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris. This show consisted of ten short films, including the Lumieres' first film Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory). This was surely a historical presentation; the first time film was shown to the public for profit. Moving pictures were no longer a fascinating optical illusion, it became a genuine art form, on the same sort of platform as theatre shows. This laid the pavement for filmmakers and animators to come, they now had a new medium with which to tell stories to large audiences.

The first public film show which charged for admission was held on December 28th, 1895, at Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris. This show consisted of ten short films, including the Lumieres' first film Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory). This was surely a historical presentation; the first time film was shown to the public for profit. Moving pictures were no longer a fascinating optical illusion, it became a genuine art form, on the same sort of platform as theatre shows. This laid the pavement for filmmakers and animators to come, they now had a new medium with which to tell stories to large audiences. One of the first great animators was Len Lye, who was famous for painting directly onto film (like Eadweard Muybridge painted onto the glass panels of his zoopraxiscope). Lye was born in New Zealand and made his way to London in 1926 by working as a coal trimmer on a steam ship. In London, he joined the Seven and Five Society. There, he made his first film "Tusalava" (1929) which documents the evolution of simple celled organic forms into chains of cells then more complex images from tribal cultures and contemporary modernist concepts.

One of the first great animators was Len Lye, who was famous for painting directly onto film (like Eadweard Muybridge painted onto the glass panels of his zoopraxiscope). Lye was born in New Zealand and made his way to London in 1926 by working as a coal trimmer on a steam ship. In London, he joined the Seven and Five Society. There, he made his first film "Tusalava" (1929) which documents the evolution of simple celled organic forms into chains of cells then more complex images from tribal cultures and contemporary modernist concepts.

(Stills from Tusalava, in which half the screen is negative and half positive)

Lye later moved on to make films for British General Post Office where he reinvented the technique of drawing directly on film with his animation for the 1935 film A Colour Box which was an advertisement for "cheaper parcel post". He didn't use a camera for anything except the title cards at the beginning of the film

Lye later moved on to make films for British General Post Office where he reinvented the technique of drawing directly on film with his animation for the 1935 film A Colour Box which was an advertisement for "cheaper parcel post". He didn't use a camera for anything except the title cards at the beginning of the film

Another animator who drew directly onto film was Norman Mclaren. Mclaren was famous for pioneering techniques including drawn on film animation, visual music, abstract film, pixilation and graphical sound. "Pixilation is a stop motion technique where live actors are used as a frame-by-frame subject in an animated film, by repeatedly posing while one or more frame is taken and changing pose slightly before the next frame or frames. The actor becomes a kind of living stop motion puppet." (Wikipedia, Pixilation). This technique is often used to blend live actors with animated ones in a movie, such as in the 1993 film, The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb by the Bolex Brothers.

So, these early animators had a kind of "clear pallet" in the sense that not much had been done with animations so that had room for experimentation. They acted like testers, seeing what was possible within the medium which set up a clear understanding of what could be done for later filmmakers to use in their own way.

Amung history-making animators, none is more famous, more notorious or more recognisable than Walt Disney.

Walt Disney was born December 5, 1901. He started The Walt Disney Company with his brother Roy Disney in 1923. Walt's first gift to animation was the storyboard, which is a series of rough sketches of a film that is produced as a template for what will happen in the film. This is very similar to the Egyptian paintings. Storyboards totally revolutionised the process of creating films since a fairly detailed plan of the film could be seen before actually started to produce it. These are still used today and are a vital part of pre-production for any film. But his maverick status isn't attributed to that one creation, Disney was also the first company to produce a film with sync-sound (sound which plays in sync with what's on screen) in the 1928 film, Steamboat Willie.

Walt Disney was born December 5, 1901. He started The Walt Disney Company with his brother Roy Disney in 1923. Walt's first gift to animation was the storyboard, which is a series of rough sketches of a film that is produced as a template for what will happen in the film. This is very similar to the Egyptian paintings. Storyboards totally revolutionised the process of creating films since a fairly detailed plan of the film could be seen before actually started to produce it. These are still used today and are a vital part of pre-production for any film. But his maverick status isn't attributed to that one creation, Disney was also the first company to produce a film with sync-sound (sound which plays in sync with what's on screen) in the 1928 film, Steamboat Willie.

(Steamboat Willie)

Steamboat Willie marked the Golden Age of Animation: the age of sound animation, with famous characters like Mickey Mouse (first seen in Steamboat Willie), Bugs Bunny, Donald Duck and others.

In 1937, Disney made their first feature length animated film, Snow White. Snow White was created with cell animation (or tradition animation) which is when eat frame is drawn by hand. It is no surprise that tradionally animated films take a long time to produce, with Snow White consisting of approximately 1.5 million drawings. Cell animation became Disney's signature style which they used to make following feature films such as Pinnochio, Fantasia, Dumbo, Bambi, Cinderella etc.

There were other companies who made the most of the golden age of animation, such as Warner Brothers, which formed in 1933. Founded by the four brothers Harry, Albert Sam and Jack, Warner Bros was another pioneer of sound on film (then known as "talking pictures" or "talkies"). Harry famously opposed talkies, wondering, "Who the heck wants to hear actors talk?" Despite the disagreements, the company was and still is one of the major film companies and produced gems like Loony Toons, within which spawned multiple famous characters like Bugs Bunny, who is still one of the most recognisable animated characters ever.

These animated characters from Disney and Warner Brothers reigned supreme through the golden age of animation, which ended in the late 1960s when theatrical animated shorts began losing to the new medium of television animation. Companies like Hannah Barbera, founded by William Hannah and Joseph Barbera, were producing short cartoons for tv which were hugely popular with children. Hannah Barbera were most famous for the Flinstones, Tom and Jerry, The Jetsons, Scooby-Doo and The Smurfs. The company dominated American television animation for nearly four decades with their "Limited animation" style which is a process of making animated cartoons whereby the animator does not redraw entire frames but variably reuses common parts between frames. One of its major characteristics is stylised design in all forms and shapes, which in the early days was referred to as modern design. This type of animation is much cheaper and quicker than traditional animation so cartoons could be churned out quickly for tv, keeping children constantly entertained. "This style of animation depends upon animators' skill in emulating change without additional drawings; improper use of limited animation is easily recognized as unnatural. It also encourages the animators to indulge in artistic styles that are not bound to real world limits. The result is an artistic style that could not have developed if animation was solely devoted to producing simulations of reality. Without limited animation, such ground-breaking films as Yellow Submarine, Chuck Jones' The Dot and the Line, and many others could never have been produced." (Wikipedia, Limited Animation).

Other popular styles that boomed at the death of the golden age include cutout animation which is a technique for producing animations using flat characters, props and backgrounds cut from materials such as paper, card, stiff fabric or even photographs.

Terry Gilliam was a popular cutout animator. Gilliam started his career as an animator and strip cartoonist. One of his early photographic strips for "Help!" (an American satirical magazine) featured future Python cast-member John Cleese. From 1969 to 1974, Gilliam was responsible for animating Monty Python's Flying Circus, which used the cutout style that spawned from Gilliam's days as a strip cartoonist. Flying Circus was a sketch show composed of surreality, risqué or innuendo humour, sight gags and observational sketches without punchlines. The cutout style worked well with this style of humour because it looks unrealistic and, well, silly.

Terry Gilliam was a popular cutout animator. Gilliam started his career as an animator and strip cartoonist. One of his early photographic strips for "Help!" (an American satirical magazine) featured future Python cast-member John Cleese. From 1969 to 1974, Gilliam was responsible for animating Monty Python's Flying Circus, which used the cutout style that spawned from Gilliam's days as a strip cartoonist. Flying Circus was a sketch show composed of surreality, risqué or innuendo humour, sight gags and observational sketches without punchlines. The cutout style worked well with this style of humour because it looks unrealistic and, well, silly.

Python stayed true with the cutout style and even featured it in their films The Holy Grail and Life of Brian. The style remained very popular since it's relatively easy and very cheap to do. Monty Python and its animation style in particular heavily influenced animators like Matt Stone and Trey Parker, the creators of South Park who originally used paper cutouts to animate in the 90s before later moving onto computer animation.

Another animation technique which gained popularity from the 60s was rotorscoping: the art of filming live action footage and then drawing over each frame to make it seem animated. This technique was popularised in The Beatles' 1968 film, Yellow Submarine. This style went on to influence hugely popular films, such as the 1985 music video for A-Ha's "Take Me On" directed by Steve Barron. This video is reknown for its animation style, which made it hugely popular at the time since the reign of MTV meant bands felt more and more pressure to create ellaborate videos. The band may not have had such success without the video which they have early animators to thank for.

Another animation technique which gained popularity from the 60s was rotorscoping: the art of filming live action footage and then drawing over each frame to make it seem animated. This technique was popularised in The Beatles' 1968 film, Yellow Submarine. This style went on to influence hugely popular films, such as the 1985 music video for A-Ha's "Take Me On" directed by Steve Barron. This video is reknown for its animation style, which made it hugely popular at the time since the reign of MTV meant bands felt more and more pressure to create ellaborate videos. The band may not have had such success without the video which they have early animators to thank for.

This style went on to influence hugely popular films, such as the 1985 music video for A-Ha's "Take Me On" directed by Steve Barron. This video is reknown for its animation style, which made it hugely popular at the time since the reign of MTV meant bands felt more and more pressure to create ellaborate videos. The band may not have had such success without the video which they have early animators to thank for.

Rotorscoping is also very time-costly, which the 2006 film "Scanner Darkly" outlined when it took 15 months to process.

Other popular styles that boomed at the death of the golden age include cutout animation which is a technique for producing animations using flat characters, props and backgrounds cut from materials such as paper, card, stiff fabric or even photographs.

Terry Gilliam was a popular cutout animator. Gilliam started his career as an animator and strip cartoonist. One of his early photographic strips for "Help!" (an American satirical magazine) featured future Python cast-member John Cleese. From 1969 to 1974, Gilliam was responsible for animating Monty Python's Flying Circus, which used the cutout style that spawned from Gilliam's days as a strip cartoonist. Flying Circus was a sketch show composed of surreality, risqué or innuendo humour, sight gags and observational sketches without punchlines. The cutout style worked well with this style of humour because it looks unrealistic and, well, silly.

Terry Gilliam was a popular cutout animator. Gilliam started his career as an animator and strip cartoonist. One of his early photographic strips for "Help!" (an American satirical magazine) featured future Python cast-member John Cleese. From 1969 to 1974, Gilliam was responsible for animating Monty Python's Flying Circus, which used the cutout style that spawned from Gilliam's days as a strip cartoonist. Flying Circus was a sketch show composed of surreality, risqué or innuendo humour, sight gags and observational sketches without punchlines. The cutout style worked well with this style of humour because it looks unrealistic and, well, silly.Python stayed true with the cutout style and even featured it in their films The Holy Grail and Life of Brian. The style remained very popular since it's relatively easy and very cheap to do. Monty Python and its animation style in particular heavily influenced animators like Matt Stone and Trey Parker, the creators of South Park who originally used paper cutouts to animate in the 90s before later moving onto computer animation.

Another animation technique which gained popularity from the 60s was rotorscoping: the art of filming live action footage and then drawing over each frame to make it seem animated. This technique was popularised in The Beatles' 1968 film, Yellow Submarine. This style went on to influence hugely popular films, such as the 1985 music video for A-Ha's "Take Me On" directed by Steve Barron. This video is reknown for its animation style, which made it hugely popular at the time since the reign of MTV meant bands felt more and more pressure to create ellaborate videos. The band may not have had such success without the video which they have early animators to thank for.

Another animation technique which gained popularity from the 60s was rotorscoping: the art of filming live action footage and then drawing over each frame to make it seem animated. This technique was popularised in The Beatles' 1968 film, Yellow Submarine. This style went on to influence hugely popular films, such as the 1985 music video for A-Ha's "Take Me On" directed by Steve Barron. This video is reknown for its animation style, which made it hugely popular at the time since the reign of MTV meant bands felt more and more pressure to create ellaborate videos. The band may not have had such success without the video which they have early animators to thank for.This style went on to influence hugely popular films, such as the 1985 music video for A-Ha's "Take Me On" directed by Steve Barron. This video is reknown for its animation style, which made it hugely popular at the time since the reign of MTV meant bands felt more and more pressure to create ellaborate videos. The band may not have had such success without the video which they have early animators to thank for.

Rotorscoping is also very time-costly, which the 2006 film "Scanner Darkly" outlined when it took 15 months to process.

In 1961, a student from MIT, Ivan Sutherland, designed a piece of software called Sketchpad, which allowed its user to draw a figure onto a computer screen using a light pen. This is the first computer animating software. Also General Motors, a car company, created a design system called DAC (Design Augmented by Computers). With it, they could look at 3D models of their cars from every angle.

The 70s saw computer animation become popular in live action movies such as Future World which included the first use of 3D animation for human hands and face. Also, George Lucas' Star Wars in 1977 used an animated 3D wire-frame graphic for the trench run briefing sequence. Lucas was always fascinated by visual effects which he perfected during his time at University of Southern California.

The first feature length film which was totally computer animated was Pixar's Toy Story in 1995. "In all, Toy Story has about 1700 shots, and each shot has been modeled,

animated, texture-mapped, shaded, lighted with a combination of proprietary and

off-the-shelf computer graphics tools (running primarily on Silicon Graphics

workstations), and rendered on rack after rack of Sun SPARCstation 20s--87

dual-processor and 30 quad-processor SPARCstations (294 processors in all)

running 24 hours a day in a special room aptly named the "Sunfarm." It's just

frame-by-frame animation, but Pixar has, somehow, imbued it with life." (Barbara Robertson, CGW Magazine - August 1995)

The first feature length film which was totally computer animated was Pixar's Toy Story in 1995. "In all, Toy Story has about 1700 shots, and each shot has been modeled,

animated, texture-mapped, shaded, lighted with a combination of proprietary and

off-the-shelf computer graphics tools (running primarily on Silicon Graphics

workstations), and rendered on rack after rack of Sun SPARCstation 20s--87

dual-processor and 30 quad-processor SPARCstations (294 processors in all)

running 24 hours a day in a special room aptly named the "Sunfarm." It's just

frame-by-frame animation, but Pixar has, somehow, imbued it with life." (Barbara Robertson, CGW Magazine - August 1995) With the invention of computers and the internet, animations can be easily produced and distributed by anyone, since animation programs are easily accessible and it's free to upload something online. In the early days of the internet, short flash cartoons were all ablaze, with animations like peanut butter jelly time becoming hugely popular. Another benefit of the internet for animators is that their work can be spread easily by their audience and become viral, ending in their work being widely recognised and quoted to the point of it being a household referrence.

With the invention of computers and the internet, animations can be easily produced and distributed by anyone, since animation programs are easily accessible and it's free to upload something online. In the early days of the internet, short flash cartoons were all ablaze, with animations like peanut butter jelly time becoming hugely popular. Another benefit of the internet for animators is that their work can be spread easily by their audience and become viral, ending in their work being widely recognised and quoted to the point of it being a household referrence.Nowadays, with social networking sites and youtube, people can share their videos with ease. The accessibility of editing software and the medium to spread work has expanding exponentially. People have made careers making animated flash series on youtube. Youtube offers people the opportunity to work for themselves and broadcast what they want without deadlines. I see 2D animation becoming something which is more for the people rather than the corporations. When we can watch endless funny cartoons on demand whenever we want with youtube, why would we bother watching them on tv?